Outdoor Idaho

50 Years of Wilderness

With the passage of the Wilderness Act in 1964, Americans began a grand experiment in land management—to set aside certain areas "where man himself is a visitor who does not remain."

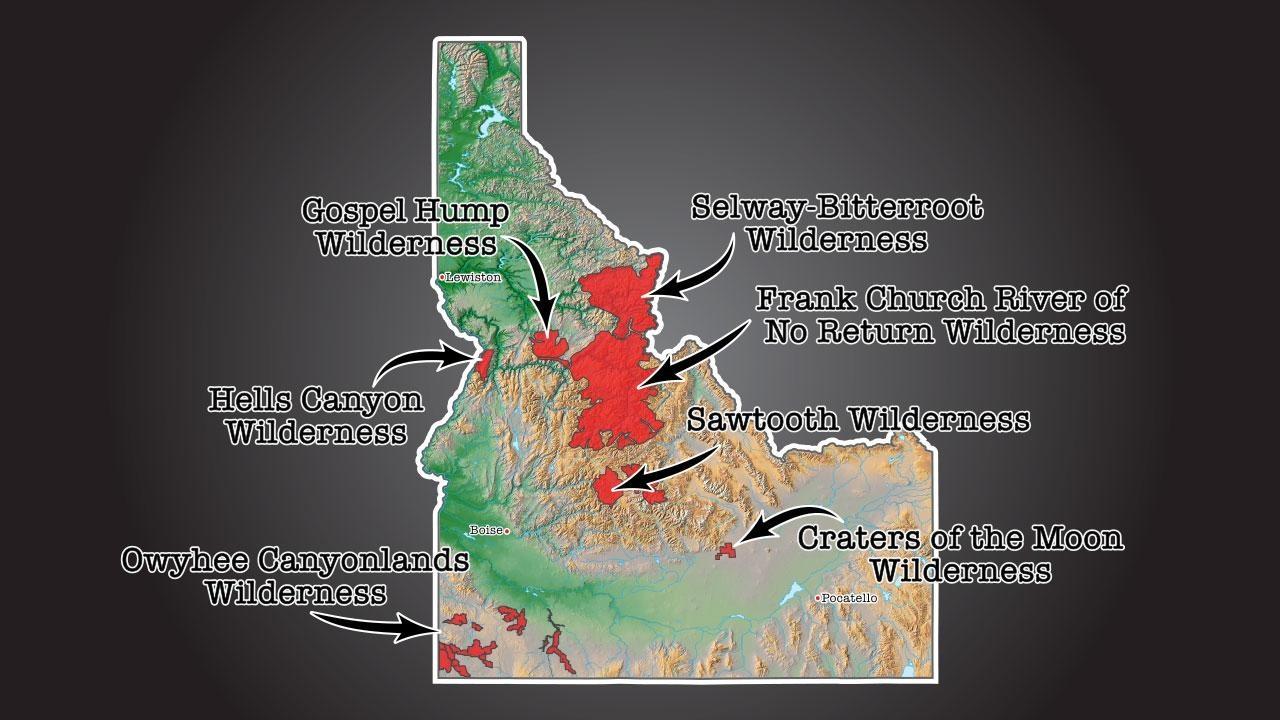

Idaho now has 4.5 million acres of official wilderness. Only two states—Alaska and California—have more.

For the 50th anniversary of the Wilderness Act, we visit each of Idaho's designated wilderness areas—the Selway Bitterroot, Craters of the Moon, Sawtooth, Hells Canyon, Gospel Hump, Frank Church River of No Return and Owyhee Canyonlands—to explore what we've learned since the passage of this landmark legislation.

And we also visit two proposed wilderness areas: the Boulder-White Clouds of central Idaho and north Idaho's Scotchman Peaks.

Is there still a constituency for wilderness? And what, if anything, needs to change?

We explore some of the issues surrounding Wilderness. And we also experience some absolutely stunning country!

We visit Idaho's wilderness areas to discover what we've learned.

What Wilderness Means to Me

My first connection with wilderness is documented by an old black and white photograph of my father toting me along on his back while fishing. I appear in a hand-sewn pack that was roped on to a standard issue Army Pack Board. The place was on the South Fork of the Flathead River where he was a guide and outfitter in a vast wild area now known as the Bob Marshall Wilderness. That old home-made pack hangs on the wall in our living room to this day.

Wild places drew him west at a young age from his home near Lake Minnetonka in Minnesota. His passion for wilderness never ended and it shaped me. The call of wilderness haunts me and I must answer . . . often. I have passed this love of wild places on to my own kids. They both spend their college summer breaks as whitewater guides on the wild rivers of Idaho. Recently my son Conner and I shared an early summer ski trek to the top of Alpine Peak in the Sawtooth Wilderness. He was on his way to report for guide duty on the Middle Fork of the Salmon river in the heart of the Frank Church Wilderness.

This love of wilderness ultimately helped shape every aspect of my life, including my business designing and marketing river boats. It all started with my selfish want of a special boat for floating the Middle Fork of the Salmon. In the wilderness. At times in life I found myself far from wilderness where fences and "Keep Out" signs dominate the landscape. It repressed that primal need to wander in wild places full of crags, snowbanks that give life to mighty rivers, alpine lakes, wild animals and roadless landscapes where it is possible to feel completely alone and very free.

I know that I am not alone in this need to escape the modern world and stumble around in wilderness. Where the iPhone does not work and the internet does not intrude.

I've been contemplating the concept of wilderness since I was asked to write a short essay about the subject. And to be quite honest, I have drawn a blank. You see, for me, I am young enough in my early forties to say that designated wilderness has always existed, at least from my perspective. Growing up I had visited the mountains of Idaho, Utah, and Colorado, and that was fine and all, but my first real taste of wild land far away from any machine, let alone anything that remotely resembled civilization was as a Boy Scout on a long hike, out in the Frank. I didn't even know what "wilderness" was, I had never experienced any thing like that. And after over fifty miles of slogging with an overloaded pack and boots that were too big, I never wanted to again. However, I made that same trip two years later and I realized then the value of wide open spaces where man is just a visitor.

Now, thirty years later I spend the majority of my "Wilderness" time in the Sawtooth Wilderness, with the occasional return to the Frank. I have even retraced my steps of those first fifty mile hikes with my own family.

Some might say it's a calling back to a simpler way of life. Out here, unplugged from the grid, the only available social network are other folks mostly doing the same thing I am. Looking to just...be.

I have lived in Idaho most of my life. I have not, however, loved Idaho for very long.

I, like so many of us, had a rough childhood filled with bullies and fighting parents. I hated living here. I left as quickly as I could and went to college in Oregon. I met and married a man and ended up in Utah. We moved constantly and everywhere, from Salt Lake City, Utah to Ontario, Oregon and half of Idaho in-between. Things always seemed worse in Idaho. He was not happy here and that made it very hard for anyone else to be happy. There was a bit of abuse involved. I existed.

In 2003 I was hired on with a contract fire crew working out of Stanley, Idaho. I had never been there before. On my way to the house the company provided, I crossed over Galena Summit for the first time in my life. I was awe-struck. Over the next few months I explored the Stanley Basin and Wood River area and got my first taste of appreciating where I lived. I had lived most of my life in the South Central area and basically knew what sagebrush-covered Idaho looked like. I bought disposable cameras and documented my adventures. I felt alive for the first time in my entire life when I was climbing mountains and sitting by Stanley Lake . . . and away from him.

Fast forward a couple years (leaving the bulk of the story out), but finally I was divorced. I was a single mom now with no child support and in and out of court constantly against him. I worked two jobs and went back to college. I bought a used, $10, 2.1 megapixel camera off eBay and made it a point to take a picture of one pretty thing a day. Slowly I opened my eyes and my mind, and started to see not only the beauty here in Idaho, but the beauty in life. I had never experienced this before.

All of a sudden colors were more vibrant, sunsets were a physical thing, and I became obsessed with capturing what I could see and feel. With the phenomenon that is Facebook, I was able to start posting pictures. When I first started posting, I did it simply for me. I was stunned when people started liking my photographs. As my photographic skills evolved, I found I had a following. This was a total surprise to me. I had always been the one hiding behind the scenes and have struggled with being in the spotlight. I appreciate each and every person who has been with me on this incredible ride every step of the way. I have now upgraded equipment, editing software, and gained an incredible amount of knowledge from where I started. I am also just beginning.

I have also been fortunate to explore more of our great state. I have sat in a camp on Basin Butte Road and watched lightning storms and snow storms over the mighty Sawtooths. I have been so in love with spots in the Frank Church Wilderness that I never wanted to leave. I have watched mountain goat kids play on virtually non-existent ledges and learn to romp in the clouds. I have seen elk, deer, wolves, coyotes, eagles, big horn sheep, and even a wolverine. I have sat in Heaven (a.k.a., the beach at Stanley Lake) and had the last rays of sunset reach out and tell me goodnight.

Last month I was blessed enough to be able to spend two weeks camping by Stanley Lake with my amazing man who loves the outdoors as much as I do. For the first time in my life I could sit there and feel complete peace. I could smell and hear and feel and touch every piece of nature that surrounded me. The energy was overwhelming. I am in Idaho. I am in love. I am happy. I am home.

I have had a love for the mountains for as long as I can remember. I am not sure how it started, but the draw of the backcountry has been a strong and consistent force in my life. This summer, I had the opportunity to introduce my oldest grandson to the Sawtooth backcountry. My son and grandson accompanied me on a backpack trip to Alice Lake. It was my grandson's first backpacking experience.

I have four sons, and they are spread out across the country. As a family we have tried to maintain a connection with the wild places by going on vacations to the mountain places we all love. We have explored the high country of Colorado, the red rock beauty of Utah, the magic and wonder of the parks of northwestern Wyoming, and the wonderful backcountry of Idaho.

My son and his family live in Houston, Texas. It is debatable as to which local feature is the highest, the dump or one of the overpasses on the freeway. When growing up, my son wandered the backcountry of Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado and Utah with me. It seems that I have passed on that love of backcountry adventure to him. His wife is a Wyoming girl from the other side of the Wind Rivers. The beauty of the west is in her DNA also. She called me one day, about a year ago, and said that at eleven years old, it was time to take Scotty, my grandson, on his first backpacking adventure. I agreed.

After discussing a number of places, we narrowed our selection to the Seven Devils or the Sawtooths. We finally decided on the Sawtooths, then honed our choice of destinations further to the Alice Lake region. I had been through that area once before and remembered it as a place of spectacular beauty.

There is a difference between camping in the wilderness and camping where you can drive a vehicle. Everyone knows that food taste better when camping. The world is fresher and there is a sense of peace. With backpacking, all of those sensations are magnified tenfold. Six miles of climbing up a mountain slope, crossing creeks with no bridges, and sleeping on a thin camping pad focus and awaken the senses. It was not an easy trip up for my grandson. He carried twenty pounds in his pack and packed it without complaint.

Alice Lake did not disappoint. The beauty was outstanding. Perhaps the beauty of the mountains is like the taste of food in the mountains. If you work hard for it, you appreciate it more.

Alice Lake does not allow open fires. There are too many people and it's too close to tree line. There is not enough wood. The area was beautiful, with no old cans or junk in the fire ring. There were no fire rings. In the morning and evening when the light is at its best, the place was beautiful. This beauty is reflected in the photos, all from the Alice Lake area.

Our backcountry journey and the Alice Lake destination made the perfect impression on my grandson. Now the hook is pretty firmly set, and I believe he too will be lured back to the mountains for the rest of his life. The experience provided by the wilderness far surpasses the experience in a drive up campground. I am personally very glad that there was a magnificent wilderness I could share with my son and grandson.

I grew up an outfitter's daughter, in what is now the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness. My dad, Jim Renshaw, was raised along the Selway River on what is now called Selway Lodge. At the time he was growing up, his parents, Alvin and Elna Renshaw, called it the 51 Ranch. They ran a dude ranch, packed for the Forest Service, raised a few head of cattle, and grew a garden. That was 1932-1948.

My mother was raised on the Oregon side of the Snake River, across and downstream from Pittsburg Landing, on Somers Creek. Her folks, Frank and Minnie Wilson, had a sheep and cattle ranch.

My Dad's parents sold out up the Selway. My mother's parents went into the business of outfitting, and it just happened that they were outfitting out of the Selway ranch when my dad went to work for them. He met their daughter, Darlene. That next summer they got married, bought the outfit, and soon bought a 51 acre homestead a couple miles up from Moose Creek Ranger Station, along Trout Creek. They built a cabin there. Us kids — there were four of us — would get to fly in for our Thanksgiving vacations. Our dad would be in there guiding hunters until after the first of December.

I helped my parents with the summer pack trips, then hunting camps. It was a great life. My parents would send me and the guests out ahead of the pack string. We enjoyed the scenery, riding the ridge tops until we reached the next camp near a high mountain lake with good fishing, savoring a long green meadow with a stream running through it. The main camp was near Fish Lake, which has an airstrip. Occasionally we'd get a surprise watermelon, or ice cream, in by way of plane.

So, I come by it naturally, it's in my blood. I'd rather be in the mountains, between the Lochsa and Selway Rivers. And if I'm not there, I may be with my dog and cameras exploring the front country, the river corridors.

My mother used to say she didn't need to travel because there was so much she wanted to see within a 100 miles of home. I agree.

I was lucky. I had the Sawtooth mountains to hook me, back when I was eleven, back when it was known as the "primitive area," long before I realized what designated wilderness meant.

It was a week-long 50 mile hike sponsored by the City of Boise, with about 15 kids and several adults on horseback. We started in Grandjean and made a big loop, hiking to Elk Lake, Ardeth, Spangle, Benedict and a dozen other lakes. We were in heaven.

After that, I spent nearly every summer hiking in the Sawtooths. My folks would drop my buddies and me off near the mountains and say, "See you in five days." One of our favorite lakes was Toxaway. I remember we latched logs together with twine an old miner gave us and floated out to the island. We also climbed to the very top of the mountain at the far end of the lake, spotting more than 20 lakes from our 10,000 foot perch. For us teenagers, wilderness was a blast. There was wonder and surprise and the feeling that we were on our own.

I have to say that today, for me, the Bighorn Crags in the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness seems a more "wild" experience. I've been there twice; and lakes like Ship Island make you really work for it. If you go, take lots of photos, 'cuz you never know when you'll be back there. You are a long way from civilization and truly, truly on your own.

But the Sawtooth primitive area was my first wilderness, and you know what they say about the glory of first love. It will always make you smile.

And it does.

My first encounter with hiking in the wilderness area was in 1977. My oldest brother, Dennis, was often gone for weeks at a time exploring the backcountry on solo trips to the Sawtooths. He and my middle brother, Richard, arranged a meeting point and time for me to join Dennis on a backpacking trip. Richard borrowed a pack for me and helped me get the supplies I would need for a four day hike. Dennis had gone up a week before to hike on his own before he was to meet up with his baby sister. We met at Petit Lake for an adventure of a lifetime.

I don't know if the offer to take me hiking included bringing my dog, but I promised he would be no problem and he kinda wanted to go too. Over the next few days we hiked the loop to Alice Lake, Twin Lakes and Toxaway Lake. I think we only saw maybe four people total the whole time we were hiking. Dennis made camp, cooked for me and supplied me (and my dog) with the use of his military issue pup tent. I remember one night it started storming and the thunder rolled. I heard a polite request from my brother, "Can I share the tent with you? I'm getting pretty wet." At some point I woke up to see my dog lying across Dennis' chest, panting like crazy and drooling because he was scared of the thunder. My dog's face was only inches away from my brother's. I slept just fine, but I think Dennis was a little short on sleep that night.

Because of the experience I had early on, my craving for hiking and exploring areas that are protected has increased the older I get. My most recent backpacking trip was last summer with a good friend who had not hiked in the wilderness before. It won't be the last trip we share together exploring what Idaho's wilderness areas have to offer.

July, 2013 was when the two lake images below were taken. I took my long-time friend, Ruth Harder, on a three day backpacking trip, her first. We camped at Alpine Lake, then hiked to Sawtooth Lake the next day. Our first night at Alpine Lake included some way happy people on the far side of the lake. They laughed a lot and played their music. They departed sometime the next day, so we wandered over to the far side of the lake to see what the view looked like from there. We found a small rock cairn . . . then proceeded to build one of our own, Ruth being the construction manager.

Our trip to Sawtooth Lake included hiking to the mouth of the lake, then back the same way we came, then traveling up over the saddle to the next valley — what a view! The next ridge had been badly burned by a fire a few years earlier, but the area shows signs of recovering nicely.

My wilderness experience is always enhanced by the company I take with me. I get to share the experience of visiting a landscape that hasn't changed much for nearly 14,000 years, altered only by the forces of nature. Sharing the wilderness allows the adventurers an opportunity to observe and to interact with the splendor of untrampled wild land and its abundant wildlife. In the end, we are rewarded with wilderness memories that last for years.

The wilderness offers us natural values. We witness watersheds that provide a cycle of life that benefits us directly in terms of natural diversity, wildlife, and inspirational landscapes. I find wilderness to be the most productive wildlife sanctuary we have, with our wildlife refuge system adding to diversity. The wilderness is a haven for the natural cycles of wildlife and perpetuates these valuable resources for all of us to enjoy.

We get to walk into the wilderness and sit, fish, hunt, photograph, paint, and build friendships. Then we return to the unnatural world with its protection and the safety of home. But the wilderness always beckons us, waiting for us to return to its many peaks, valleys, and waterways, to receive our reward, each in our own way.

Over the years our family has built lasting memories together enjoying Idaho's great outdoors — camping, fishing, hiking, boating, or soaring over Idaho's beautiful landscape in our small plane.

It has only been within the last three years that I have discovered the joy of landscape photography. It has opened up a whole new world to me, and I've sought never to miss a sunrise or a sunset. My husband and I take every opportunity to escape the chaos of daily life and head to the mountains to explore another pristine lake or back road hide-away.

I'm beginning to wonder if backpacking is dead. During recent trips to some of Idaho's wild areas, I saw few hikers. And in non-wilderness areas, many people were getting around in ways that aren't allowed in wilderness areas. What this says to me is that a lot of backpacks are being left behind in the closet. Has backpacking's time in the sun passed?

I was a teenager in the early seventies. Back then, backpacking meant more than just camping out. It was a way of connecting with the natural world and refreshing your soul. I remember in the summer of 1973, a friend and I went hiking for three days in Maine around Mount Katahdin. We battled blisters, mosquitos, crummy food and equipment. We measured ourselves against the wilds of northern New England. It was a great trip. We experienced solitude and long conversations that helped deepen our friendship. This hike symbolized to me what backpacking was all about.

In hindsight, this era was probably the highpoint for backpacking. A few years earlier, America had celebrated its first Earth Day, and John Denver's "Rocky Mountain High" was a top ten hit. Putting on your backpack and getting in tune with the woods was a symbol of the times. Henry David Thoreau would have been proud!

Four decades later, the state of backpacking seems very different. Some people are still opting for outdoor experiences, but quicker daylong jaunts — like mountain bike rides — seem to be the norm. More troubling are the increasing number of people opting to live life virtually, on the web.

This summer, I went on two hikes that symbolize to me how people are using, or not using, our wild areas. In July, I journeyed ten days across the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness in central Idaho with friend Jeff Tucker. A week later, I hiked four days into the White Cloud mountains. They were a study in contrasts.

The Frank hike entailed traversing its borders — from west to east — about 87 miles in total. I followed Big Creek River down to its confluence with the famed Middle Fork of the Salmon River, and then up into the Bighorn Crags. During the first six days, I passed an average of one other hiking party a day, outfitted groups with pack animals about the same. Since the Frank is a designated wilderness area, both motorized and mechanical devices, like mountain bikes, are prohibited. The Frank seemed like what you would expect from a wilderness area . . . a whole lotta land, and not many people.

The White Clouds trip was a very different experience. This area is not wilderness, but has many wilderness-like attributes. It is part of a broader swath of land under consideration for Monument protection status by President Obama. But it differs from The Frank because motorized and mountain bike access is allowed along designated corridors.

As I entered the White Clouds from the Little Boulder Creek trailhead, I saw several outfitted trips with pack animals, long distance trail runners, motorized trail bike users and dozens and dozens of mountain bike riders on day rides. What about backpackers? I saw a few. The takeaway for me was that not many people are hiking these days, and they're utilizing methods that aren't allowed in traditional wilderness areas.

For me, backpacking is alive and well. Just like in 1973, I tested myself against the rugged land, gazed at immense vistas and spent some wonderful time with friends. This is to me what makes backpacking so special.

For me I find that the wilderness experience reaches its zenith when I go out on my own and challenge nature one on one. Many call that foolish and irresponsible; I call it exhilarating. The key is not to push yourself beyond what you expect of yourself. Yes, I know things happen that are beyond your control, and in situations like that it is best to have a companion. But if you are out there setting personal goals for yourself, which can only be achieved by going solo, then the rewards outweigh the risks. At least for me they do. I do enjoy taking trips with others and sharing experiences and gaining valuable friendships, but there are also times I need to go out on my own and answer the "call of the wild".

I know there are many reasons why people go "into the wilderness" — to "find oneself," to find "God," to get away from the hustle and bustle of everyday life, to hunt, to share camaraderie . . .

But whatever the reasons, we all have ones that are just our own. Mine have changed over the years. I used to love to get out to where I would find the fewest people, clear my head, and fish. Now I love to get out to where I will find the fewest people, clear my head, and take photographs. Some of the photos I share with you, others I keep in my mind to myself and hold dearly. Those images can never be taken away.

The main reason I go to the wilderness though is because I feel comfortable there, and because I was meant to be there. I do not feel whole if part of me is missing. To become "whole," I need that alone time where my thoughts are not interfered with by outside influences (i.e., people). Again, some call me crazy. Maybe I am.

I moved to Mackay in October 2006 from NE Ohio when my husband was transferred to INL. I just looked on a map, called a number listed in the Arco Advertiser and ended up renting an old church in Mackay. I was certain we had ended up in a different world.

Although I considered myself well traveled, I didn't realize places like Custer County still existed. My husband is from NW Colorado so he felt right at home. We somehow survived minus 40 degree temperatures in a house with little heat, and that spring we finally had the opportunity to explore the beauty around us.

We bought a house which provides us a daily look at the Lost River Range, especially Mt. McCaleb. We have explored many of the wilderness areas around Custer County, and there are so many more to be discovered — Hidden Mouth Cave, Pass Creek, Trail Creek, Copper Basin, the Sawtooths, Wildhorse, Upper Cedar Creek, Iron Bog, and many alpine lakes. We are planning to climb Mt. Borah this summer.

For me this move has been transformative — a forced slow-down of a hectic life and an appreciation for this wonderful place which we call home. We love the community and the access to world-class fishing, hiking and biking. I'm not sure I can ever go back to my previous way of life.

I'm glad that some people have been able to see far enough into the future to set aside wilderness areas. It can seem in this "modern age" we live in that "it's all been done." Humanity has trod the Earth beneath its collective feet. There are no more places left to explore, to conquer, to be the first to set foot upon.

Wilderness, particularly wilderness areas in Idaho, have been of great value in my own life. Yes, someone went ahead of me, and did the exploring and mapping and blazing and naming. Yet, for many reasons, they couldn't tame the lands, or they decided they wouldn't tame the lands. They saw the value in leaving them untamed for people who would follow in their footsteps. People like me.

Wilderness journeys have given me an opportunity to see places where few have gone, to be in places that can only be reached by foot or hoof or paddle or wing. Idaho's wilderness areas have beckoned to me with their call, and are still beckoning me.

My first wilderness backpacking trip was to He Devil Lake with Idaho Mountain Search and Rescue (IMSARU) in 1965. Several members of the unit planned on climbing He Devil Peak after reaching the lake. It turned out to be a long trip in thanks to getting slightly disoriented. We came out the route we should have gone in close to Mirror Lake.

When my oldest son Stevie was a baby my wife Gale and I used to take him into the Seven Devils in a special backpack for infants. We moved to Lewiston, and learned that one of our neighbors, Bud VanStone, backpacked and fished high mountain lakes every chance he got. We decided we had a lot in common and started joining him on his excursions. For 30 years we have experienced many of Idaho's great wilderness areas together.

Almost 50 years later I'm at the top of He Devil with two of my three sons, Chris and Trever, and my dog Molly. We decided to place a memorial for my son Nate who was killed in a car accident earlier in the year. This is the umpteenth time my boys and I have backpacked into the Seven Devils.

We also discovered Gunsight Lake in the White Clouds, another favorite place to go backpacking.

I'm not a rugged outdoorsy adventurer. Still, wilderness has been part of my summers for many, many years — hikes with friends, backpacking with my kids, even a few solitary day trips. That I make the effort to find my way there speaks to how I value the perspectives and challenges of being in these primal and uncivilized and achingly beautiful places.

On an intellectual level, wilderness is near the top of my list of "What 'we, the people' and our government need to do" to take care of our planet. Identifying wilderness areas and treating them differently than other forests and mountain areas is about so much more than recreation. Wilderness areas provide critical protection for watershed origins, wildlife, and entire ecosystems. The "Big W" designation sets aside areas for very constrained use, as it, more importantly, protects those areas from particular abuses. The Wilderness Act has served its purpose for the past 50 years by providing a process to cordon off wild preserves.

I, along with most probably, idealize wilderness as unchanging even as the world around it changes. But it's simply not true. The changes in those wild areas have been hardly noticeable until more recently. The "hands-off" management — letting nature take its course — worked only until it became unavoidable that settlement and industry, energy, pollution — all those effects of expanding human population — grew to impact even those areas on our planet where humans are not. Now there is a different need to balance the ideal with a new reality. Preservation is not possible without active management that can address invasive weeds, fire, and whatever yet unknown threats.

"Big W" wilderness is not just an alternative to a theme park, a health spa, or a spiritual retreat. To me, it denotes a responsibility for being placed on this planet at this point in time. A time when our civilization gives us the power to change the world, literally, even as it gives us the technologies for easy living. Protecting wilderness — the experience and the ecosystem that exists even without people there to experience it — is the price we need to pay for our lives of privilege.

In 1984 I was working a summer job on the Green River below Flaming Gorge Dam — great job. We went to Vernal to get some groceries and culture and decided to take in a movie. Pale Rider was playing, and that opening scene of the cowboys riding full bore at the base of those amazing peaks made me stay until the ending credits to see where Clint had done his filming. "We would like to thank the Sawtooth National forest for all their cooperation on this film." I want to live THERE!!

Fast forward to October of 1988, and I have my dream job with Idaho Fish and Game at Sawtooth Hatchery at the base of the Sawtooths in Stanley, Idaho. Does a kid from Iowa believe in divine intervention? You bet he does. On my first real big game hunt in Idaho we trekked up the East Fork of the Salmon River. That unforgettable first day I saw nine species of big game!

I will never live back in Iowa. Wilderness exists to make me feel small, insignificant. I love that feeling. I love the cleansing silence of wilderness. I dream of Lewis and Clark and the Corps of Discovery surviving in what is now Idaho. I envy them.

I have always loved exploring the wilderness, especially trails, not knowing where they will go. When my girls were small it was a big deal to get on a dirt trail just to see where it would end up and what we might find around the next corner or over the next hill. Would we see wildlife, would we come across a hidden lake or waterway, would we find a new place to picnic or camp, would we get lost . . . just what treasures would we find? The anticipation of what we might see or find kept us going and going.

Idaho's wilderness is more than a place for recreation. It is the best place I have found for inspiration, for filling my soul with joy and God's peace. Idaho has much to be explored, and I know I will never get to see it all, but not for a lack of trying. It is more to be admired and enjoyed than used. Idaho's wilderness is full of surprises.

My fantasies about being in the wilderness began when as a child I would watch The Little House on the Prairie show in black and white. I lived in Los Angeles for almost thirty years. Two years ago, my wife and I moved to Garden Valley. When I knew we were moving to the mountains of Idaho, I started watching that show again to prepare me mentally for the change of habitat and the cultural shock I was about to experience.

As I watched the show, my childhood fantasies of exploring wilderness with creeks, barns and wildlife started to surface again. Now they've actually come true as I explore the wilderness of Idaho on my photo treks with my dog Barkley. I had never fished in my life, and to my surprise, I actually caught two trout the first time while camping.

The Stanley Lake area and the Sawtooths have been my favorite places until recently when I made a trip to Blue Lake in the Cascade area. The view from the trailhead captured my eye and my camera lens. As I hiked around the rocky ridge, I found some wildflowers growing among rocks in a very late June afternoon.

Idaho's wilderness is a photographer's dream come true, and for two years now I have been photographing it. My bucket list of places to photograph continues to grow as does my love for the rich and diverse places Idaho has to offer. As a photographer, I find myself going alone on my photo trips. When accompanied by people who are not photographers, they may grow weary of the photographer's patience to wait for the right lighting, to set up a tripod and play with exposures and different angles. The same can be true even when accompanied by other photographers, since their style and patience may differ. So I have learned to cherish my solitude in the wilderness even though it can be dangerous at times. Some of the places are only accessible by quad, and on those occasions even my dog can't come along.

Hiking in the spring and summer is my favorite wilderness activity while I carry my camera, tripod and backpack around. Photographing elk is another activity I will never tire of. Living in Garden Valley I see great herds in the fall and spring, but it is a scene that will never become too familiar. I love it when photographing a herd — how the leader makes eye contact with me and stands guard to see if I'm a threat or not, or as if posing majestically. I was intimidated once by a deer in my own backyard when I had been in the mountains for just a couple of months and had never interacted with wildlife before. I was photographing him at about 50 feet and he started stumping. I was naïve and thought he was posing. He went from stumping to hissing at me. He won because I realized he was not happy; I went in the house!

The many hot springs of Idaho are another enjoyable thing that the wilderness offers. My favorite is the one with a waterfall at Pine Flats between Garden Valley and Lowman which has a great view of the South Fork of the Payette River.

I no longer have to fantasize about The Little House on the Prairie or The Swiss Family Robinson. I am now living my own wilderness fantasies and photographing them!

Interviews

Tom Tidwell is the current Chief of the U.S. Forest Service. Tidwell began his Forest Service career on the Boise National Forest as a firefighter and has spent more than 30 years dealing with forest issues. This interview was conducted by Bruce Reichert in October of 2014.

It seems like the concept of Wilderness could be a little hard to accept for an agency that favors multiple use.

Well, actually, it's not. If you look back on the history, it was the early Forest Service employees that really started the Wilderness movement, the designation of areas. Going back to 1920 with Aldo Leopold, Gila Wilderness came out of his efforts, quite a few years before the Wilderness Act.

And yet the Wilderness Act was created in part because the Forest Service administratively could and did backtrack on Wilderness.

And there's no question. The legislative process to designate Wilderness provides more certainty, by far. It's supported by law. And so those were some of the questions about our administrative approaches that said, yes, Forest Service, you acknowledge these areas need to be reserved, preserved as is; however, things could change administratively in the future. So, that was the benefit and really what was the driver behind the Wilderness Act.

Most folks assume a hands-off approach in our Wilderness areas, and yet, in the future, we may need to manage them more if we want to keep the characteristics we love. Will Wilderness require more management in the future?

Well, in the future we're going to have to definitely use more fire, to help restore and maintain the resiliency of these systems. We also need to inform the public so they have a greater awareness to be careful about bringing invasives into areas. And then when we do get a problem, we can go in there and just use volunteers and hand-pull those weeds. And for the most part, the majority of our Wilderness areas still have very intact ecosystems, and you actually see less invasives, less weeds in those areas, because of that intact ecosystem.

Many people seem quite concerned that the Wilderness is burning up, and that no one is doing anything about it.

Well, fire is part of the ecosystems, and it is the tool, the only tool we have to be able to restore the health and resiliency of these systems. And there's no question, over the decades of fire suppression, we have changed the fire regimes. We've changed the makeup of plant composition in there by keeping fire out. So now our challenge is to put fire back in there. And, luckily, here in Idaho and the Frank Church and also in the Selway-Bitterroot, we've seen the difference by being able to manage natural fires. So, today when we get a large fire started, yes, it burns, but it will burn into one of the old burns that slows down, it creeps across there, and we're able then to have fire in the system to help promote the overall health.

In the past decade or two, we seem to be reaping the effects of putting out all the wildfires, as a matter of public policy, for almost a century.

We are. And there's no question, we're in a catch-up mode, not only in our Wilderness areas but throughout the national forests, to be able to manage more fire on the landscape; but we need to manage it. So, when we get a natural ignition, folks need to understand that we're going to be watching it, and we'll take what steps we need to, to make sure it kind of stays where we want it to be and it burns under those conditions. And that's the thing folks need to be okay with. They need to be able to trust that we are managing it and that we're going to do everything we can so that it doesn't ever threaten their communities.

I think a lot of people would be surprised that the Wilderness Act allows fire suppression. You can fight fires in Wilderness.

There's nothing in the Wilderness Act that prohibits fire suppression at all. In fact, we can go in and use mechanized equipment if we need to. Most places we don't. But in some of our Wilderness areas that are very close to urban areas, if that's what it takes to be able to keep the fire from coming out, we're going to do that.

But the best thing we can do is to be able to manage the natural ignitions so that when we do get a fire started, it's going to burn at a much lower severity. It's much easier to stop if it does come out. And at the same time, it has less of an impact on the overall watersheds. The forest is able to recover a lot faster, and that's what we need to do, and the best tool is by using fire.

The hot Wilderness topic in Idaho, of course, is the Boulder-White Clouds. Within the next year, it appears we're going to have either a national monument there or Congressman Simpson's wilderness proposal, CIEDRA. Have you taken a position?

There is significant difference between designating an area as Wilderness and a national monument. There's no question that Wilderness designation provides the highest level of protection, and it's covered under law. There's a lot of certainty there.

Now, there's benefits with the national monument, too. It can do different things that allow more flexibility than what a Wilderness designation can do. But I think what's really important here, and what I heard from the congressman, is that folks here in Idaho, they want to see some level of protection.

Ideally, I think the Wilderness legislation is the right way, the best place to go forward to really honor that collaborative effort. But at the same time, we need to respond to what we're hearing from the public, and the public is telling us they want some additional protections.

The other part of this is to basically honor some of the compromise that's been developed through these collaborative efforts. The legislation would do that, and as we move forward to have the discussions with communities about a monument designation, that's also one of the things we want to talk about, about how to be able to honor those compromises, those agreements that have been put in place through this collaborative effort.

So, you seem to be leaning more towards Simpson's wilderness proposal than a national monument at this point.

I want to honor the work that's gone on, and there's no question that when it comes to protecting areas, in the times that I've spent in the Boulder-White Clouds, you know, that has Wilderness character. And I just want to make sure that not only my daughter but her kids and maybe the next generation has that same opportunity to go back into a place like that. So, that's probably the best.

With that being said, in this administration the President's been very clear, that where we have situations like we have here with CIEDRA, where there's been strong collaborative come-together, legislative language put forward, bills introduced, but we're not able to move forward with it, there is a good opportunity then for the President to use the Antiquities Act. We did it in Colorado with a place called Chimney Rock, and it was based on legislation that was introduced. Last week we announced the one in Southern California, the San Gabriel. It was based on a legislative approach, and there wasn't any action on that. But it really is just to respond to what the public wants.

What do you see as the real threats to Wilderness in the next 20 years? Is it fire? Is it noxious weeds? Is it climate change? Is it a public that loves motorized travel?

With fire, as we continue to do the work we're doing -- and we're treating millions of acres each year to restore these forests both inside Wilderness and also with outside -- so 20 years from now, we're going to be caught up, and we'll be in a much better place to be able to deal with the fire.

Probably my greater concern with Wilderness, I want to make sure it's still relevant. I want to make sure, like the students that I was talking to this morning in the conference, that they have the passion, that they understand the benefits of these areas, this intact Wilderness; and whether it's to do the research that's in there or to provide that solitude, it's so important. There's no question, it is part of our heritage. It's part of our culture. And I really do believe it is part of the American spirit.

But that's the thing I want to make sure, that Wilderness, the concept of Wilderness, is relevant 20 years from now, 40 years from now; and I think that's a challenge that we have. We need to be able to elevate the understanding and the awareness, especially with the youth of today.

That's a tough one, because the youth of today are looking for their reality on their cell phones and their iPads and their motor bikes. How do you appeal to those kids?

One way we're working on that is through our youth programs. Last year we employed over 10,000 youth across the country, to give them an opportunity to get out and do some work in the national forests and out in the Wilderness areas, so they have an understanding of what conservation's all about. And no matter what they do with the rest of their lives, whatever career path they take, I think that time spending even a few weeks out there can really make a difference; and hopefully some of them will actually come to work for the Forest Service. But whatever they do, that's so important. So, that's one way that we can connect.

The other part is that we've got to learn how to use social media, and when it comes to Wilderness, there's a lot of debate going on. If you're reading the Sand County Almanac from the book you packed in, or if you're reading it off of your iPad, is there a difference? Definitely with some folks there is. But those are the things we need to talk about and really take a step back. And what is the real value of Wilderness? And part of it is to be able to keep it relevant and also to provide access, and if that access is through some forms of social media, then that's something I think we need to embrace.

The work that you do through Idaho Public Television is a great way to be able to share not only the values of Wilderness but why it's important, because I know that there's a lot of people that will never step one foot into a Wilderness area, but they're very strong advocates, strong supporters of it because of what it means to them, just knowing that it's there, and those are the things we're going to have to continue to work on.

Do you ever see a time when the Forest Service will have the money to do what most experts believe needs to be done in Wilderness and in our forests? Do you see any bright spots?

Well, I do see bright spots, and I continue to always be optimistic. But to be fair, we've never had enough resources to do everything. And one of the things that I stress with our employees and with our communities, that we need to feel good about the progress that we're making.

I'll tell you, the differences that are occurring today, we're seeing more and more people that want to be engaged, either to volunteer or actually contribute their own resources, financial resources and their own time, because they want to be part of it. They want to be part of the collaborative processes, but they also want to get out there and help. Those are the things that also provide a lot of optimism with me about where we're headed.

I think it's just a matter of time in this country when we fully recognize the benefit of these landscapes, the value of the clean air, the clean water, the biodiversity, the wildlife and fish habitats, the recreational settings, the quality of life that it provides, plus all those economic benefits that occur from managing those lands. And when we recognize that, then I think there'll be the resources that we need to be able to care for these lands in the way that the American people want them cared for.

Well put. But the opposition is still there.

Well, there's no question, this concept of collaboration — and I'll tell you, it's nothing new, but I'm really proud of the agency, how we've embraced this over the last five or six years, so that it's really commonplace. It's not an easier way, but it's a better way, to take the time to bring diverse interests together and to be able to work out and reach an agreement. Not only do we make better decisions, but then people support those. And when they don't work out as planned, then you've got a whole crowd, you've got a community that's standing with you to say, "Okay, let's learn what didn't work, and let's go back to the table and fix it."

It does take time. And as much as I, at times, think, you know, Wilderness should not be controversial, but it is so important in that it's really permanent protection, and so we do need to take the time to make sure that we select the right area. And that is so helpful, not only to have the right boundaries that we can actually administer, but it really reflects what the community wants. And I'll tell you, where I've worked in places where the community is supported, I'll tell you, it's so much easier, so much better. Not only is the management, the care for the Wilderness, but you have that support, and then you also see more economic benefits in those communities that actually support Wilderness than those communities that have some questions about it.

There really aren't any northern Idaho Wildernesses. You worked there. Is there hope for Scotchman Peak being ultimately in the Wilderness camp?

I think if the collaborative stays together and people are willing to invest the time, then I think it will get done. And the reason I say that is that I've been up there in those communities, and I can remember when people couldn't even stand to be in the same county together, and now they're not only sitting together, they're working together. And not only are we seeing more agreement about what areas should be Wilderness, but also how we should be actively managing other parts.

So, the communities up there are seeing a difference. They're seeing an improvement in the overall forest health. They're seeing the outputs of sawtimber and biomass coming out there which is creating jobs. It's keeping the industry in place so we can actually restore the resilience of these forests. And so people are seeing the benefits of actually coming together. And I think folks are tired. They're tired of the controversy and some of the fight that really didn't solve anything, and because of that, I think we'll get there someday, but I think it'll take a few years. But it's worth it, because once Wilderness is designated, it's permanent, and it needs to be permanent, so it's worth spending the time to do it right.

So, I'm wondering how you keep a stiff upper lip in face of all the adversity that Mother Nature throws at you, and all the controversy over how best to manage our public lands. How do you keep your team from racing to take early retirement?

Well, there's more support for the Forest Service mission of being able to not only provide the benefits, but to provide the services. There's more support for that today than ever in my entire career. There's less controversy. There's less conflict. There's more people coming together; and whether it's around Wilderness or around what we need to do to restore these forests. And I'll tell you, that's the difference.

And I'll tell you, this is the most exciting time in my career, and I've spent most of my career dealing with the conflict, but today there's more and more support where people are sitting down together, reaching solutions and we're moving forward to not only increase and improve the management of the national forests but also to improve the service. So, that's what keeps me going. This is, in many ways, the best time — the best time in my career, and I'll tell you, that's what keeps us coming to work every day.

Last question: you made an appeal to Idahoans today at the Frank Church Conference.

The appeal I made this morning, it was kind of based on my experience with the Idaho Roadless Rule. And I'm on record as saying that I didn't think that was going to work out. I'm from Idaho. But I'll tell you, that group — and it was kind of a formal collaborative -- I'll tell you, they impressed me. They found resolution around that issue, and I use it as an example. If we can do that on 9 million acres of roadless in this state, the idea that we can come together to identify which areas should be Wilderness, so that was my ask.

I think Idaho can set the example. They can be the model, like they have been in the past, about there's a better way to do this. And the big part when it comes to Wilderness, getting the designation, it provides certainty. And so a lot of folks that are concerned about what it is or what it's not, getting it completed also answers that question. So, there's benefits for everyone that's interested in this, and so that's kind of my expectation. We've done it before. There's no reason we can't do it again.

Craig Gehrke is the regional director of the Idaho office of the Wilderness Society. He was a key player in the 2009 wilderness designation of Idaho's Owyhee Canyonlands, the state's first wilderness legislation in nearly 30 years. This interview was conducted by Bruce Reichert in the summer of 2014.

We've had designated wilderness now for 50 years. What has it meant to the nation?

Wilderness designation is a commitment to a landscape that I think really helped define what America was. We don't have to develop everything in order to be a wealthy nation. Wealth isn't just about money. Wealth is also about spirit, and it's about heritage.

The thing about wilderness that I've come to appreciate is that there's no good or bad in it. It just is. We get carried away with trying to put our values on a landscape, and I think that's the wrong thing to do. I think you have to take wilderness on its own terms and leave your values behind when you come in and experience the wilderness. You're there to learn from it, not there to make judgments.

And what do you think it's meant to Idaho to have 4 ½ million acres of wilderness?

The wilderness system protects and preserves and keeps the best of what really makes Idaho unique. There are places where people say, this is really what defines our state, like the Middle Fork Canyon, Hells Canyon, the Sawtooths. We can't improve on that. We want other people to see this. We want people to come after us to say, this is really a great spot in our state, and it's always going to look like this.

Is there one thing that folks don't understand about wilderness?

That you take wilderness on its own terms. You don't come in and decide what ought to be there. The idea that we bring our artificial targets for elk populations into a wilderness area, we bring our artificial goals for wolf populations into wilderness -- that's not what wilderness is about.

Wilderness is about what happens to the land when we step back and appreciate it and try to learn from it. We can take those lessons and apply them to other landscapes that we do more intensively manage. I'm a big believer that we need places in the West that we learn from and we don't try to manipulate. Good baseline information -- what does the western landscape look like without big manipulation -- is very valuable to us, and it's something that we don't take advantage of enough or appreciate enough.

How important is it to the Wilderness Society that there be more wilderness?

Specific places don't protect themselves; if they are going to remain undeveloped, there's got to be a proactive approach to it. People have to step forward and say, "Okay, this place right here deserves to be protected."

And the whole emphasis behind the Wilderness Act was that leaving it to agency flexibility wasn't going to cut it. Here in Idaho the Forest Service removed places from primitive areas before they were designated wilderness. That really brought groups like the Wilderness Society and the Sierra Club to say we need a more permanent system, because to endure the political winds was going to take an act of Congress to set this up and not leave it just to the agencies to manage.

The Forest Service was opposed to wilderness right up until the bitter end where, I would argue, they saw the inevitability of it. They didn't like it. It was a problem. And even for years afterwards, I remember back when I started my career, wilderness was really not necessarily a career move for a Forest Service person. It's gotten a lot better the last few generations.

Are there places that you think today deserve the designation of wilderness?

I think in the short term, they've done a fabulous job around Scotchman's Peak to build local support for Scotchman's, and I think that's just a matter of time. I mean, they've gotten grassroots support for a wilderness designation.

I think the Great Burn on the Idaho and Montana border is another great candidate that's been recommended for generations now for wilderness. Borah Peak should be wilderness. It's been recommended. So, I think there's lots of different spots around Idaho that are going to come and be in the wilderness system at some point.

Are you worried that a younger generation may not have the same feelings about wilderness that you have?

It's tough, and I kind of believe this is somewhat cyclical, too. I think we're kind of in a downswing right now, and that's unfortunate because, like I said, areas don't protect themselves. They need constituencies.

I think the challenge for groups like the Wilderness Society is to find more opportunities to get younger people to places like Idaho and see what we've got here. Until we did the Owyhees, the idea of wilderness and the discussion about it was off the table for a long time. People come here now and they kind of take it for granted, "Oh, yeah, those are cool places. They've always been there." Well, it was tough.

So, I think trying to get people to appreciate that wilderness areas are the unique places they are is part of an educational process, and I think as people stay in Idaho and they come here, they get to know those places, and I'm counting on an upswing.

It seems that most of our current wilderness areas have involved bitter fights.

And, see, that's the point we make about all of these designations that they're incredibly controversial, and that's okay; but they're also looked upon as the right thing to do.

It's important to remember that when the final passage for the Frank Church Wilderness came about, Frank Church was the only one who voted for it out of the four members of the delegation. He didn't let the lack of agreement stop him and stop that effort, and I think that's important. At some points you'd need to step forward with a longer term vision and do the right thing.

Nobody in their right mind today would argue for more damns on the Snake River. Nobody in their right mind would argue for a molybdenum mine at the base of Castle Peak. Very controversial, but, in hindsight, these are Idaho's icons.

You raised some eyebrows when you hooked up with mountain bikers to push a White Clouds monument without any wilderness in it.

I'll be honest. It was a tough decision. The Wilderness Society has argued for support of wilderness in the White Clouds for decades now. One of the first conservation actions I took as a student at the University of Idaho was signing a petition to make the Boulder-White Clouds wilderness, back in the early 1980's. So, backing off from wilderness came as a recognition of how dysfunctional our Congress is.

Also, I'm a firm believer that places do not protect themselves, that if you want a place to remain as it is today, it takes a proactive approach. Just thinking, "Well, you know, the Forest Service will manage it okay" -- that's not going to happen. If you look at the last 30 years, there's no question that that's been eroding.

Mountain bikers hardly existed, you know, 15 years ago. Now they're a constituency with a seat at the table. And so the decision for the monument came saying, "All right, let's work with the constituencies there and talk about managing all the uses there." Nobody wants the trails in the White Clouds to be overrun by bicyclists, so I'd rather be having them with us to make a decision about how to manage a monument after it's done than just leaving it the way it is right now, which, basically, you show up, you get to ride.

There's a fellow in Lewiston that's converting dirt bikes over to snow travel, and will the Forest Service say, "No, you can't do that" in a wilderness study area of the White Clouds? Well, they've got a pretty poor record of that right now.

For folks like me who value solitude, silence, wildness -- to leave it the way it is now, you're going to lose that over time. You've got to step forward. People have got to step forward and say, "Okay, we're going to manage this or we're going to protect that kind of character."

I think a monument can do that now. It's not going to be wilderness, but I'm convinced that five years from now, a monument in the Boulder-White Clouds is going to be better than they would be if we don't step forward and do something. Look at the different constituencies that helped to get Hells Canyon passed, like the jet boaters. That wouldn't have happened without the jet boaters, so we kind of talked about the mountain bike was our jet boat moment.

We need these people to protect the White Clouds at this point in time, and they came forward and said, "Well, let's talk about the trails here. Let's talk about how this might work." We had some pretty productive discussions that led to the agreement, that we'd support some trails that have been left open, and they'll support some trails that are being closed in the Monument, so it worked out at this point in time.

I imagine you got a few calls from your wilderness buddies.

We did, and we still do, and it's been hard. I'll be honest. It's been hard to motivate the folks who have worked for generations for wilderness to accept less than wilderness, but again, it gets back to the process we've counted on, which is Congress. It's broken. Nothing's going to happen.

There's a lot of folks that say, "Well, if you do a monument, you shut the door on wilderness forever." That's not technically true, but I'll be the first to admit that once you protect an area, for all intents and purposes, it's protected that way. You know, coming and taking the second bite of the apple could conceivably happen, but there's not been much history of that.

So why couldn't advocates push Rep. Simpson's wilderness bill for the Boulder-White Clouds over the finish line?

It was very frustrating when Congressman Simpson couldn't get the White Clouds through, because that had everything going for it. It had a constituency; it had buy-in from the County; it had pieces that everybody was better off than they were without the bill. And to see that just sink under the partisan wrangling that we see now was very disappointing, because a lot of us -- and particularly Congressman Simpson -- spent years putting that package together.

I think there were seven versions of it; it kept getting better all the time from our standpoint. He got to the point where he should have been able to get over the finish line and just didn't quite make it.

It was interesting that the Owyhees made it through and the White Clouds didn't. Talk about your dark horse! Nobody knew where the Owyhees were; they couldn't even pronounce "Owyhee." And suddenly that one passed, and the White Clouds didn't, even though the White Clouds have been, since 40 years ago, looked at for wilderness.

What if the president had just quipped, "Oh, we're looking at Monument status in Idaho's White Clouds"?

Part of it was we kept hoping that we could get wilderness. We didn't push for Monument until we had a bit of a realization, "This isn't going to happen. You know, this is not going to happen." And we still thought, because there had been so much work gone into Simpson's bill, that we could resurrect it. We could get enough momentum again, get something moving through Congress. Then everything stopped moving through Congress, from budget bills to wilderness bills to anything. They weren't doing anything, and that avenue just seemed to be walled off to us.

I'm wondering if we can really afford wilderness in the 21st century, if it's all just going to burn up or become infested with noxious weeds.

It is going to burn. You know, Yellowstone burned. Forests have been burning for generations, and they'll continue to burn. There's not much we can do about it. That's where you've got to step back and just say, "Okay, we can't stop this, you know. It's just going to happen. What can we take from it? What can we find out about that, about this landscape here?"

But you're right. If you look at a map for the Frank Church, most of it has burned now to the point where I would argue that you're not going to get this scale of fire anymore, because you've got a bit of mosaic, and you've got places where fire doesn't burn as intensely. Now climate change will probably change that, because we're going to have different burning conditions that we've never seen before.

And what about weeds?

Some folks would argue, "Well, just let the weeds go. You know, you just have to watch and see what happens." Other people would say, "Well, we're supposed to be providing for wildlife and fish habitat, and a lot of these weeds don't supply forage for anything."

So, that's the balancing act where they're trying to keep the status quo, but the long-term success of that, I think, is really up for debate. We've supported weed control on the Middle Fork, along the Selway, along the main stem, but I've got to admit, when you see other places in Idaho, the Lower Salmon or the canyon with yellow starthistle, you've got to kind of wonder, "Is this all inevitably going to change very dramatically and for the worse?"

So management is the answer?

It will require some manipulation, some management, and it almost makes you think, at what point can we not keep it the way it is? What point does it become not wilderness but become a relic of what was? And that's not their management goal either, but that's kind of how we think about it. I want this place to look like it does when I saw it and when my kids saw it, and I'm not too sure that's going to work out long-term.

That's depressing.

Well, it's the whole global change thing. Protecting wilderness doesn't do anything for global warming other than give us, like I said, some kind of benchmark to judge what we've done to the planet. But after working all these years, inevitably, they're going to burn. You're going to see more weeds. You're going to see some wildlife leave. You know, will mountain goats survive in Idaho 50, 60 years from now? I don't know. I don't know.

I imagine this problem of weeds is a real concern in the Owyhee Canyonlands, our newest wilderness.

I think the potential problems down there will be fire, and this gets into the fact that I think our fire regimes are changing. And that's going to be a place where the BLM is going to really have to think hard about how they're going to manage fire, because you've seen what happens between Boise and Mountain Home. Repeated fires wipe out sagebrush.

Some of the best sagebrush and sage-grouse habitat are like in Big Jack's and Little Jack's Creek, and so that would make an argument for a more proactive fire suppression in these wilderness areas, because we can't afford to lose any more of the sage-grouse habitat. So, that's going to be one of the balancing acts that I think the BLM faces, that we're all going to face, is maybe a free fire regime is a luxury we can't afford in the Owyhee Canyonlands, because that would mean the loss of sagebrush and sage-grouse. And are we willing to make that sacrifice?

So, you can't just take a hands off approach to wilderness. Any decision is a decision that's going to affect the land down there, and just letting fire go down there has some long-term ramifications for altering that ecosystem to cheatgrass.

You seem so pragmatic about wilderness. So it doesn't mean a "hands off" approach to land management?

It's never been that way. That's kind of the myth. And I think, actually, the opponents try to say, "Yeah, you're going to lock that up and then it's just going to go to hell, you know, burn up, whatever." And that's not how it's ever been.

Even with fire back in the 70's and 80's, there were conscious decisions of what lightning strikes they were going to go in and suppress. And look at the Middle Fork. You're managing 10,000 people down that river every year. That's not a hands off.

So what are the "myths" of wilderness?

Boy, it's hard to start on the myths about wilderness. We've heard everything from you can't do search and rescue, you can't hunt, you can't pick berries. You can't maintain trails. I mean, over the years, it's mostly just put forward to scare people. And I think it's gotten better in the more recent years, because I just think there's more people that know what wilderness is all about.

But I remember back in the early 1980's where even people like Representative Craig was saying you can't maintain trails in a wilderness area; and we're just constantly putting out these little brush fires of misinformation. It's just mostly promoted by the opponents trying to scare people.

So you can fight wildfires in wilderness?

You can fight fires in wilderness. You can put them out. You can jump on them. You can let them go; like a lightning strike now, they'd probably leave it alone. A lightning strike a month from now, I don't know. It's going to be interesting this year.

Any last thoughts?

It used to be that pioneers felt they were surrounded by a sea of wilderness. Now wilderness is surrounded by a sea of people; and you've got air pollution affecting alpine lakes.

And that's another concern, that there are more people living in the West and coming to these places. That's going to affect wilderness areas; how are we going to deal with that? Those are going to be some tough questions.

Earl Dodds was the first ranger on the newly formed Big Creek District of the Payette National Forest, serving in that position from 1958 until his retirement in 1984. The Big Creek District, originally part of the Idaho Primitive Area, became part of the River of No Return Wilderness in 1980. Dodds wrote a book about his experiences, "Tales from the Last of the Big Creek Rangers," which is available on the Payette National Forest website. This interview was conducted by Marcia Franklin in July of 2014.

What about this country attracted you so much that you wanted to work here for so long?

The big geographic feature in this whole area is the Salmon River. It is very difficult to say too many good things about the Salmon River. It's all within one state, which is really kind of unusual. It has no dams on it; it's an entirely free-running river. It has a fishery that is outstanding. In addition to the fishery it has big game, and it is really a tremendous resource. And in fact, even though it's entirely within Idaho and it's Idaho's river, it's a national treasure. It really is.

I think it's truly a unique feature and (I had) a real outstanding opportunity to be involved with the management of this place back here.

The area you administered used to be called the Idaho Primitive Area. Tell me about that.

The intent of the whole Idaho Primitive Area was to set aside something and keep it in an undeveloped state, so there weren't any roads constructed during that time, and there's no logging. But it was very long on fire control, and at that time the number one priority in most of the districts in the West was fire control.

So the area was considerably opened up from that extent and there were quite a system of trails and lookouts and telephone lines, and the whole objective was to catch the fires while they were very small and keep 'em that way.

And then the Wilderness Act was passed. What was that like?

It took quite a long time, like eight years, to debate the provisions of the Wilderness Act through the Congressional process back there in Washington D.C. and finally get it signed. But when it did come to a vote finally it had overwhelming support. There was a really great interest in doing it and setting something aside and keeping it in a wild state.

You often hear the conservation services say America's best idea was the national parks. I'll bet you the Wilderness Act is not too far behind that. In years to come we're going to be recognized as maybe the #2 best idea (tears up).

You get emotional talking about it don't you?

I do get a little emotional talking about it.

Why is that?

I just really believe in the wilderness movement. I'm a strong supporter of the wilderness movement and keeping it undeveloped.

Tell me more about why you feel wilderness is so important.

Well, for one thing, once it's gone, it's gone. You can't get it back. So hold onto it as long as you possibly can. Keep your options open there. You know, once it's opened up and has the systems of roads and logging and so forth, the country has changed dramatically. And we've got a huge amount of that already, but this wilderness resource is dwindling.

And you had a privilege to be one of the few people right there at the beginning.

That's really right. It was really an opportunity and a privilege and, and almost like an honor here. This central Idaho unit was the largest in the lower 48 states and this Big Creek/Chamberlain District is one of the biggest pieces of that. So it was really quite an opportunity to move that from the Primitive Area management status over to this new Wilderness Act philosophy.

Did you feel at the time that you had a great responsibility?

Well, yeah, I felt we were in for a sea change here as far as management direction goes. The big emphasis on fire control and all of the lookouts and jumping on these fires was kind of taking a backseat here. We were running into, "Hey, we're going to manage this now as wilderness."

And fire control, it didn't change completely overnight, but we got to recognize that fires are a part of the natural environment back here and the fires were here way back in Lewis and Clark's day. And before the Forest Service nobody was taking action to put out forest fires. And we were going to allow fire to play a more natural part in the management areas. So that was really a major change.

What was it like working with the trail crews?

One of the things I really liked being a ranger back here was the opportunity to work with the younger guys because a lot of them this is their first time really away from home to do anything and they take right to the big country too, and they like the idea of being back here in this living condition.

Occasionally I used to get a hold of one or two, I can remember one guy had packed clear out to Lookout Mountain and about two weeks later said, "Come get me; I can't take any more of this." There are those types and there are the other ones that this is kind of the high point in their life and they come back year after year.

What were some of the other challenges transitioning from the Primitive Area to wilderness?

One of the things we started on was a program of "pack it in, pack it out" here with all the camp provisions. And that was kind of a radical change here. The Forest Service ourselves, we never packed things out when we'd camp. We buried everything and we encouraged all of the public and the outfitters and guides who pack in a tremendous amount of groceries in the course of a long big game season back here to bury their trash, too.

(The new "pack it out" program) was kind of a real unpopular program with the crew. Nobody particularly likes to handle a bunch of old icky rusty old garbage and tin cans and so forth. And I had to kind of lean on the guys to get behind the program there. The packer, he didn't like the idea of packing that old rattly stuff there on the mules. And then we got it into Chamberlain and the pilots they sure didn't like putting that old icky stuff in their airplane.

And then it was unloaded at the McCall airport, and it worked fine as long as you could back a Forest Service pickup up to the airplane and then throw it in there and haul it away to the dump, but that didn't happen all the time. Had it piled around the airport and the airport manager thought that was terrible. So it was really a kind of a tough time there.

But we stuck with it, and by golly we packed out a small mountain of trash out of Chamberlain.

I'm really kind of proud of the American public and the way they have changed their ways here on that. Particularly with the floating group. A lot of those campsites are used almost nightly, and by golly, they pick those things up clear down to picking up cigarette butts and toothpicks and very small micro-trash.

What was it like for you to have to change your living conditions to comply with the requirement of the Act that you be non-mechanized?

It was a major change there. Out went the power saws and all that, we flew 'em back, put 'em in the fire cache there in McCall, and we did away with the generator, and we got a push mower here to mow the lawn there at Chamberlain. We got rid of the tractor and we had to replace it with something, so we went and got a couple of matched mules that were broke to pull the mowing equipment very much like the farmers did all over the country before the days of the tractor.

I think what the strategy now is, "Hey, let's not have so many people (employees) back here." If you have people there, then they need things like washing their clothes, they need all the flying for the groceries and so forth, and we're trying to cut down on that activity. So the real way to do it is to not have as many people.

And I find that hard to live with myself because in my day the Forest Service it was the dominant presence back here. We had the system of lookouts and we had to maintain the trails to them, so we had trail crews out there. And if visitors came back in here they had a contact with Forest Service personnel. But now they've cut down on the number of people there to the point where we are no longer the dominant presence back here. Which kind of bothers me.

Existing airstrips were grandfathered into the Wilderness Act, even though planes are clearly mechanized. What do you think about them?

Well, that was very much incompatible with the wilderness concept. That was one of the big debates, and it held up action on the wilderness bill for a long time. I think the airplane is here to stay back here. Personally I think we've kind of overdone it here with so many strips along Big Creek there.

How do you balance the idea of wilderness with also making it possible for people to enjoy it?

Well, I strongly believe that if the wilderness movement is going to prevail and we're going to be able to keep it and it's going to be able to grow, it's going to have to have a broad base of public support. Not just a few elite people who will go to the South Pole or climb Mount Everest or something like that. It's going to have to have a much broader appeal to the outdoor public.

Part of that is the public has got to be able to use it to a certain extent. And I'm not talking about making the trails into bridal paths. We haven't developed the trails to be like a boulevard by any means. You can expect to get your feet wet while you wade through across the creek or you get an occasional log to work around. But it's not just one jumble after another, you know, or completely abandoned.

If people do come back in here and holy smokes, that was the worst darn trail they'd ever been over, by golly they have a negative experience and their support for the movement falls off.

Why did you decide to write a book?

My kids were after me. "Gee whiz, dad, you've got all those stories. Why don't you write 'em down and write 'em up for us?"